Introduction to Photolithography Technology

Development History of Photolithography Technology

Since Jack S. Kilby invented the world's first integrated circuit on September 12, 1958, integrated circuits have experienced rapid development for more than 50 years. The minimum line width is now between 20 and 30nm. time, entering the deep submicron range. Photolithography technology, one of the key technologies, has also evolved from the initial use of magnifying lenses similar to those in photographic equipment to today's immersion-type 1.35 high numerical aperture, which has the ability to automatically control and adjust imaging quality, with a diameter of more than half a meter and a weight of half a ton. giant lens set. The function of photolithography is to print semiconductor circuit patterns onto silicon wafers layer by layer. Its idea comes from the long-standing printing technology. The difference is that printing records information by using ink to produce changes in light reflectivity on paper. , while photolithography uses the photochemical reaction of light and light-sensitive substances to achieve changes in contrast.

Printing technology first emerged in the late Han Dynasty in China. More than 800 years later, Bi Sheng of the Song Dynasty made revolutionary improvements and transformed fixed block printing into movable type printing, which then developed rapidly. Nowadays, laser phototypesetting technology has been developed. "Photolithography" in the current sense began with the attempts of Alois Senefedler in 1798. When he tried to publish his book in Munich, Germany, he discovered that if he used oil pencil to draw illustrations on porous limestone and moistened the undrawn areas with water, the ink would only be Glue where you drew with pencil. This technique is called Lithography, or drawing on stone. Lithography was the forerunner of modern multi-registration.

Basic methods of photolithography

Although there are some similarities, photolithography in integrated circuits uses light instead of ink, and the areas with ink and without ink become the areas with light and without light on the mask. In the integrated circuit manufacturing industry, lithography is therefore also called photolithography, or lithography. Just as oil-based ink is selectively deposited on limestone, light can only pass through the transparent areas on the mask, and the projected light is recorded on a light-sensitive material called photoresist. A simple schematic diagram of the photolithography process is shown in Figure 7.1.

Because the photoresist undergoes a change in dissolution rate in the developer after exposure to ultraviolet (UV) light, the pattern on the mask is transferred to the photoresist layer on the top of the silicon wafer. The areas covered by the photoresist can achieve further transfer of the mask pattern by preventing further processing (such as etching or ion implantation).

Since 1960, photolithography technology can be divided into the following three types: contact exposure, proximity exposure and projection exposure. The earliest one was contact or proximity exposure, which was the mainstream of manufacturing until the mid-20th century. For contact exposure, since there is theoretically no gap between the mask and the top of the silicon wafer, resolution is not a problem. However, since contact will cause defects due to wear of the mask and photoresist, people finally chose proximity exposure. Of course, in proximity exposure, although defects are avoided, the resolution of proximity exposure is limited to 3μm or larger due to the presence of gaps and light scattering. The theoretical limit of resolution of proximity exposure is

Among them,

k represents the parameters of the photoresist, usually between 1 and 2;

CD represents the minimum size, that is, the critical dimension, which usually corresponds to the minimum resolvable spatial period line width;

λ refers to the exposure wavelength;

g represents the distance from the mask to the gap on the photoresist surface (g = 0 corresponds to contact exposure)

Since g is usually greater than 10μm (limited by the surface flatness of the mask and silicon wafer), the resolution is greatly limited, such as 3μm for a 450nm illumination wavelength. Contact exposure can reach 0.7μm.

In order to overcome the dual difficulties of defects and resolution, a projection exposure scheme was proposed, in which the mask and silicon wafer are separated by more than several centimeters. Optical lenses are used to image the pattern lens on the mask onto the silicon wafer. As the market demands for larger chip sizes and stricter line width uniformity control, projection exposure has also gradually evolved from the original

full silicon wafer exposure to full silicon wafer scanning exposure (see Figure 7.2 (a))

step-and-repeat exposure (see Figure 7.2 (b))

step-and-scan exposure (see Figure 7.2 (c))

The whole silicon wafer 1:1 exposure method has a simple structure and does not require high monochromaticity of light. However, as the chip size and silicon wafer size become larger and larger, and the line width becomes finer and finer, the optical system cannot project the pattern onto the entire silicon wafer at one time without affecting the imaging quality, and block exposure becomes inevitable.

One of the block exposure methods is the whole silicon wafer scanning method, as shown in Figure 7.2 (a). This method continuously scans and exposes the pattern on the mask to the silicon wafer through an arc-shaped field of view. The system uses two spherical mirrors with the same optical axis, and their curvature radius and installation distance are determined by the requirement of no aberration.

However, as the chip size and silicon wafer size become larger and larger, and the line width becomes finer and finer, 1x exposure makes it increasingly difficult to make the mask with high pattern production accuracy and placement accuracy.

Therefore, in the late 1970s, a reduced magnification, block exposure machine came into being. The chip pattern is exposed to the silicon wafer one by one, as shown in Figure 7.2 (b). Therefore, this exposure system with reduced magnification is called a step-and-repeat system or stepper.

However, as the chip size and silicon wafer size become larger and the line width control becomes more stringent, even the technical capabilities of the stepper cannot meet the needs. Solving the contradiction between this demand and current technology directly led to the birth of the step-and-scan exposure machine, as shown in Figure 7.2 (c). This device is a hybrid that combines the advantages of the early full-wafer scanning exposure machine and the later step-and-repeat exposure machine: the mask is scanned and projected instead of projected at once, and the entire silicon wafer is also exposed in blocks. This device transfers the optical difficulties to high mechanical positioning and control. This device has been used by the industry to this day, especially in the production of semiconductor chips at 65nm and below technology nodes.

The main lithography machine manufacturers in the world are ASML in the Netherlands, Nikon and Canon in Japan, and other non-full-size lithography machine manufacturers, such as Ultrastepper.

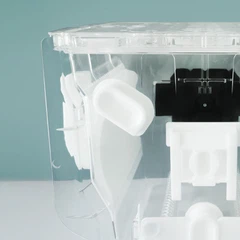

The manufacturing of domestic advanced scanning lithography machines started late. After 2002, it was mainly developed by Shanghai Microelectronics Equipment Co., Ltd. (SMEE). Domestic lithography machines have developed from repairing second-hand lithography machines to independently developing and manufacturing lithography machines. The most advanced lithography machine currently under development is the 193nm SSA600/20 (see Figure 7.3). Although there is still a large gap with the world's advanced level, it should be said that gratifying progress has been made. Its numerical aperture is 0.75, the standard exposure field is 26×33mm, the resolution is 90nm, the overlay accuracy is 20nm, and the 300mm production capacity is 80 pieces per hour.

Other image transfer methods

It is well known that one direction for the continued development of photolithography is to reduce the wavelength. However, this effort has been hampered by factors such as the development of suitable 157nm photoresists, mask protective films (pellicles) and the production volume of lens materials such as calcium fluoride (

). However, in the past 20 years, people have invested a lot of research in extreme ultraviolet (EUV) wavelength photolithography. This technology uses 13.5nm extreme ultraviolet light emitted by xenon or tin plasma generated by strong lasers or high-voltage discharges. Although the high resolution brought by EUV technology is very attractive, this technology also has many technical difficulties, such as the mirror is easily contaminated by the splash material generated by the pulse, the extreme ultraviolet light is easily absorbed (requiring the system to have extremely high vacuum and the minimum number of reflective lenses), the stringent requirements for the mask (no defects and high reflectivity), the flare caused by the short wavelength, the reaction speed of the photoresist and the resolution, etc.

In addition to using traditional light to transfer the mask pattern, people are also looking for other microlithography methods, such as X-ray, nanoimprint, multi-electron beam direct writing, electron beam, ion beam projection, etc.

System parameters of photolithography

Wavelength, numerical aperture, image space medium refractive index

It was mentioned earlier that the resolution of proximity exposure deteriorates rapidly as the distance between the mask and the silicon wafer increases. In the projection exposure method, the optical resolution is determined by the following formula, that is,

Among them,

represents a proportional coefficient that characterizes the difficulty of the photolithography process. Generally speaking,

is between 0.25 and 1.0. This is actually the famous Rayleigh formula. According to this formula, the optical resolution is determined by the wavelength λ, the numerical aperture NA, and the process-related

. If you need to print a smaller pattern, the method used can be to simultaneously reduce the exposure wavelength, increase the numerical aperture, reduce the

value, or change one of the factors. In this section, we will first introduce the existing results of improving resolution by reducing the wavelength and increasing the numerical aperture. How to improve the resolution by reducing the

factor under the premise of fixed wavelength and numerical aperture will be discussed later.

Although short wavelength can achieve high resolution, several other important parameters related to the light source must also be considered, such as luminous intensity (brightness), frequency bandwidth, and coherence (coherence will be described in detail later). After comprehensive screening, the high-pressure mercury lamp was selected as a reliable light source because of its brightness and many sharp spectral lines. Different exposure wavelengths can be selected by using filters of different wavelengths. The ability to select a single wavelength of light is crucial for photolithography, because a general stepper will produce chromatic aberration for non-monochromatic light, resulting in a decrease in image quality. The G line, H line, and I line used in the industry refer to the 436nm, 405nm, and 365nm mercury lamp spectra used by the exposure machine, respectively (see Figure 7.4).

Since the optical resolution of the I-line stepper can only reach 0.25μm, the demand for higher resolution has pushed the exposure wavelength to a shorter wavelength, such as the Deep UltraViolet (DUV) spectrum of 150-300nm. However, the extension of high-pressure mercury lamps in the deep ultraviolet is not ideal, not only because of insufficient intensity, but also because the radiation in the long-wavelength band will produce heat and deformation. Common ultraviolet lasers are also not ideal, such as argon ion lasers, because excessive spatial coherence will cause speckle and affect the uniformity of illumination. In contrast, excimer lasers have been selected as ideal light sources for deep ultraviolet due to their following advantages.

(1) Their high power output maximizes the productivity of the lithography machine;

(2) Their spatial incoherence, unlike other lasers, eliminates speckle;

(3) High power output makes it easy to develop suitable photoresists;

(4) Optically, the ability to produce deep ultraviolet output with a narrow frequency (as narrow as a few pm) makes it possible to design high-quality all-quartz lithography machine lenses.

Therefore, excimer lasers have become the mainstream illumination light source on integrated circuit production lines of 0.5μm and below, and the earliest report was published by Jain et al. In particular, the two excimer lasers, krypton fluoride (KrF) with a wavelength of 248nm and argon fluoride (ArF) with a wavelength of 193nm, have shown excellent performance in terms of exposure energy, bandwidth, beam shape, life and reliability. Therefore, they are widely used in advanced step-and-scan lithography machines, such as ASML's dual-platform Twinscan XT: 1000H (KrF), Twinscan XT: 1450G (ArF) and Nikon's NSR-S210D (KrF), NSR-310F (ArF).

Of course, people are still looking for shorter wavelength light sources, such as the 157nm laser generated by fluorine molecules

However, due to the difficulty in developing suitable photoresists, mask protective films (pellicles) and the production volume of lens material calcium fluoride (

), the 157nm lithography technology can only extend the semiconductor process by one node, that is, from 65nm to 45nm; while the previous development of 193nm lithography technology extended the manufacturing node from 130nm to two nodes: 90nm and 65nm, resulting in the final abandonment of the efforts to commercialize mass production of 157nm lithography technology. The development of exposure wavelength with process nodes is shown in Figure 7.5.

In addition to shortening the exposure wavelength, another way to enhance resolution is to increase the numerical aperture (NA) of the projection/scanning device.

Where n represents the refractive index in the image space, and θ represents the maximum half angle of the objective lens in the image space, as shown in Figure 7.6.

If the medium of the image space is air or vacuum, its refractive index is close to 1.0 or 1.0, and the numerical aperture is sinθ. The larger the angle of the objective lens in the image space, the greater the resolution of the optical system. Of course, if the distance between the lens and the silicon wafer remains unchanged, the larger the numerical aperture, the larger the diameter of the lens. The larger the lens size, the greater the manufacturing difficulty and the more complex the structure.

Usually, the maximum achievable numerical aperture is determined by the manufacturability and manufacturing cost of the lens technology. At present, the typical I-line scanning lithography machine (ASML's Twinscan XT: 450G) is equipped with a lens with a maximum NA of 0.65, which can distinguish dense lines of 220nm and a spatial period of 440nm. The highest numerical aperture of krypton fluoride (KrF) wavelength is 0.93 (ASML's Twinscan XT: 1000H), which can distinguish dense lines of 80nm (160nm spatial period). The most advanced ArF lithography machine has a numerical aperture of 0.93 (ASML's Twinscan XT: 1450G), which can print 65nm dense lines (120nm spatial period).

As mentioned earlier, the numerical aperture can be increased not only by increasing the aperture angle of the lens in the image space, but also by increasing the refractive index of the image space. If water instead of air is used to fill the image space, the refractive index of the image space will be increased to 1.44 at a wavelength of 193nm. This is equivalent to increasing the 0.93 NA in air to 1.34 NA at once. The resolution is improved by 30% to 40%. Therefore, a new era of immersion lithography began in 2001. The most advanced commercial immersion scanning lithography machines are ASML's Twinscan NXT: 1950i and Nikon's NSR-S610C, as shown in Figures 7.7 (a) and 7.7 (b). The situation of immersion lithography will be described in detail later.

Representation of photolithography resolution

It was mentioned earlier that the photolithography resolution is determined by the numerical aperture and wavelength of the system, and of course it is related to the photolithography resolution enhancement method related to the factor

. This section mainly introduces how to judge the resolution of the photolithography process. We know that the resolution of the optical system is given by the famous Rayleigh criterion. When two point light sources of the same size are close to each other, the distance from their center to center is equal to the distance from the maximum value to the first minimum value of the light intensity of each light source imaged by the optical instrument, the optical system cannot distinguish whether it is two or one light source, as shown in Figure 7.8. However, even if it meets the Rayleigh criterion, the light intensity in the area between the two point light sources is still lower than the peak value, with a contrast of about 20%. For a line light source, when the width of the light source is infinitely small, for an optical system with a numerical aperture of NA and a wavelength of the illumination light source of λ, the light intensity distribution on the image plane is

That is, the light intensity reaches the first minimum point relative to the central position of the image (2NA). I0 represents the light intensity at the center of the image. It can be considered that the minimum distance that this optical system can resolve is λ/(2NA). For example, when the wavelength is 193nm and the NA is 1.35 (immersion), the minimum resolution distance of the optical system is 71.5nm.

Of course, for the photolithography process, does it mean that a pattern with a spatial period of 71.5nm can be printed? The answer is no. There are two reasons:

① A process requires a certain margin and process indicators to be mass-produced;

② The commercial manufacturing accuracy of all machines and equipment and the comprehensiveness of machine performance, so that the machine can print dense lines at the resolution limit and isolated patterns, and must also minimize the impact of residual aberrations on the process.

For a 1.35 NA lithography machine, ASML promises that the minimum spatial period of the pattern that can be produced is 76nm, that is, 38nm dense lines with equal spacing. In the photolithography process, the limit resolution is only of reference value. In actual work, we only talk about how large the process window is in a certain spatial period and a certain line width, and whether it is sufficient for mass production. The parameters that characterize the process window will be discussed in detail in Section 7.4. Here is a brief introduction. Usually, the parameters that characterize the process window include exposure energy latitude (EL), depth of focus or depth of focus (DOF), mask error factor (MEF), overlay accuracy, linewidth uniformity, etc.

Exposure energy latitude refers to the maximum allowable deviation of exposure energy within the allowable range of line width variation. For example, for a line with a line width of 90nm, the line width changes with energy by 3nm/mJ, and the allowable range of line width variation is ±9nm, then the allowable range of exposure energy variation is 9×2/3=6mJ. If the exposure energy is 30mJ, the energy latitude is 20% relative to the exposure energy.

The depth of focus is generally related to the performance of the focus control of the lithography machine. For example, the focus control accuracy of a 193nm lithography machine, including the stability of the machine's focal plane, the field curvature of the lens, astigmatism, leveling accuracy, and the flatness of the silicon wafer platform, is 120nm. Then the minimum depth of focus of a process that can be mass-produced should be above 120nm. If the influence of other processes, such as chemical-mechanical planarization, is added, the minimum depth of focus needs to be improved, such as 200nm. Of course, as will be discussed later, the improvement of the depth of focus may be at the expense of energy margin.

The mask error factor (MEF) is defined as the ratio of the deviation of the silicon wafer line width due to the line width deviation on the mask to the deviation on the mask, as shown in formula (7-5).

Normally, MEF is close to or equal to 1.0. However, when the spatial period of the pattern approaches the diffraction limit, MEF will increase rapidly. Too large an error factor will cause the line width uniformity on the silicon wafer to deteriorate. Or, corresponding to the given line width uniformity requirement, the mask line width uniformity is too high.

Overlay accuracy is generally determined by the stepping, scanning synchronization accuracy, temperature control, lens aberration, and aberration stability of the moving platform on the lithography machine. Of course, overlay accuracy also depends on the recognition and reading accuracy of the overlay mark, the influence of the process on the overlay mark, the deformation of the process on the silicon wafer (such as various heating processes, annealing processes), etc. Modern lithography machine stepping can compensate for the uniform expansion of the silicon wafer, and can also compensate for the non-uniform distortion of the silicon wafer, such as the "grid mapping" GridMapper software launched by ASML. It can correct the distortion of the nonlinear silicon wafer exposure grid.

Line width uniformity is divided into two categories: uniformity within the exposure area (intra-field) and uniformity between exposure areas (inter-field).

Line width uniformity within the exposure area is mainly determined by mask line width uniformity (transmitted through mask error factor), energy stability (during scanning), illumination uniformity within the scanning slit, focus/leveling uniformity for each point in the exposure area, lens aberration (such as coma, astigmatism), scanning synchronization accuracy error (Moving Standard Deviation, MSD), etc.

Line width uniformity between exposure areas is mainly determined by illumination energy stability, uniformity of silicon wafer substrate film thickness distribution on the silicon wafer surface (mainly due to uniformity of glue coating and uniformity of film thickness brought by other processes), flatness of silicon wafer surface, uniformity of developer-related baking, uniformity of developer spraying, etc.

Photolithography process flow

The basic 8-step photolithography process flow is shown in Figure 7.9.

step01-HMDS surface treatment

step02-Gluing

step03-Pre-exposure baking

step04-Alignment and exposure

step05-Post-exposure baking

step06-Development

step07-Post-development baking

step08-Measurement

1. Gas silicon wafer surface pretreatment

Before photolithography, the silicon wafer will undergo a wet cleaning and deionized water rinse to remove contaminants. After cleaning, the surface of the silicon wafer needs to be hydrophobized to enhance the adhesion between the silicon wafer surface and the photoresist (usually hydrophobic). The hydrophobic treatment uses a material called hexamethyldisilazane, with a molecular formula of (CH₃)3SiNHSi(CH₃)₃,The vapor of hexamethyldisilazane (HMDS) is produced. This gas pretreatment is similar to the use of primer spray on wood and plastic before painting. The role of hexamethyldisilazane is to replace the hydrophilic hydroxyl (OH) on the surface of the silicon wafer with hydrophobic hydroxyl (OH) through chemical reaction.OSi(CH₃)₃.To achieve the purpose of pre-treatment

The temperature of gas pretreatment is controlled at 200-250℃, and the time is generally 30s. The gas pretreatment device is connected to the wafer track for photoresist processing, and its basic structure is shown in Figure 7.10.

2. Spin-coated photoresist, anti-reflective layer

After gas pretreatment, photoresist needs to be coated on the surface of the silicon wafer. The most widely used coating method is the spin coating method. The photoresist (about a few milliliters) is first transported to the center of the silicon wafer by a pipeline, and then the silicon wafer will be rotated and gradually accelerated until it stabilizes at a certain speed (the speed determines the thickness of the glue, and the thickness is inversely proportional to the square root of the speed). When the silicon wafer stops, its surface is basically dry and the thickness is stable at a preset size. The uniformity of the coating thickness should be within ±20Å ("Å, pronounced "angstrom", is a unit of length in particle physics. 1Å is equal to

m, which is one tenth of a nanometer) at 45nm or more advanced technology nodes. Usually, there are three main components of photoresist, organic resin, chemical solvent, and photosensitive compound (PAC).

Detailed photoresist will be discussed in the chapter on photoresist. This section only discusses basic fluid dynamics. The coating process is divided into three steps:

① Transport of photoresist;

② Accelerate the rotation of the silicon wafer to the final speed;

③ Rotate at a constant speed until the thickness stabilizes at the preset value;

The final photoresist thickness is directly related to the photoresist viscosity and the final rotation speed. The viscosity of the photoresist can be adjusted by increasing or decreasing the chemical solvent. Spin coating fluid mechanics has been carefully studied.

The high requirements for photoresist thickness uniformity can be achieved by fully controlling the following parameters:

① Photoresist temperature;

② Ambient temperature;

③ Silicon wafer temperature;

④ Exhaust flow and pressure of the coating module;

How to reduce coating-related defects is another challenge. Practice shows that the use of the following process can significantly reduce the occurrence of defects.

(1) The photoresist itself must be clean and free of particulate matter. Before coating, it must be A filtration process is used, and the pore size of the filter must meet the requirements of the technology node.

(2) The photoresist itself must not contain any mixed air, because bubbles will cause imaging defects. Bubbles behave similarly to particles.

(3) The design of the coating bowl must structurally prevent the splashing of the ejected photoresist.

(4) The pumping system for delivering photoresist must be designed to be able to suck back after each delivery of photoresist. The function of the suction back is to suck the excess photoresist from the nozzle back into the pipeline to avoid excess photoresist dripping on the silicon wafer or excess photoresist drying up and causing granular defects during the next delivery. The suction back action should be adjustable to prevent excess air from entering the pipeline.

(5) Wafer edge debonding (Edge The solvent used in the Bead Removal (EBR) process needs to be well controlled. During the spin coating process of silicon wafers, the photoresist will flow to the edge of the silicon wafer and from the edge of the silicon wafer to the back of the silicon wafer due to centrifugal force. A circle of bead-shaped photoresist residue will form at the edge of the silicon wafer due to its surface tension, as shown in Figure 7.11. This residue is called edge bead. If it is not removed, this circle of bead will peel off and form particles after drying, and fall on the silicon wafer, the silicon wafer conveying tool and the silicon wafer processing equipment, causing an increase in the defect rate. In addition, the photoresist residue on the back of the silicon wafer will stick to the silicon wafer platform (wafer chuck), causing poor adsorption of the silicon wafer, causing exposure defocus, and increasing overlay errors. Usually, an edge removal device is installed in the photoresist coating equipment. The function of removing the photoresist at a certain distance from the edge of the silicon wafer is achieved by rotating the silicon wafer at the edge of the silicon wafer (one nozzle on the top and one on the bottom, and the position of the nozzle from the edge of the silicon wafer is adjustable).

(6) After careful calculation, it was found that about 90% to 99% of the photoresist was spun off the silicon wafer and was wasted. People have tried to pretreat the silicon wafer before spinning the photoresist on the silicon wafer using a chemical solvent called propylene glycol methyl ether acetate (molecular formula CH₃COOCH(CH₃)CH₃OCH₃), PGMEA). This method is called resist reduction coating (RRC). However, if this method is used improperly, defects will occur. Defects may be related to chemical impact at the RRC-photoresist interface and contamination of the RRC solvent by ammonia in the air.

(7) Maintain the exhaust pressure of the developer or developer module to prevent the splashing back of tiny droplets of developer during the development process when the silicon wafer is rotated.

Since the viscosity of the photoresist changes with temperature, different thicknesses can be obtained by intentionally changing the temperature of the silicon wafer or photoresist. If different temperatures are set in different areas of the silicon wafer, different photoresist thicknesses can be obtained on a silicon wafer. The optimal photoresist thickness can be determined by the law of line width and photoresist thickness (swing curve) to save silicon wafers, machine time and materials. The discussion of swing curves will be discussed in subsequent chapters. The method and principle of spin coating of anti-reflective layer are the same.

3. Pre-exposure baking

After the photoresist is spin-coated on the surface of the silicon wafer, it must be baked. The purpose of baking is to drive away almost all the solvents. This baking is called "pre-exposure baking" or "pre-baking" because it is performed before exposure. Pre-baking improves the adhesion of the photoresist, improves the uniformity of the photoresist, and controls the line width uniformity during the etching process. In the chemically amplified photoresist mentioned in Section 6.3, pre-baking can also be used to change the diffusion length of the photoacid to a certain extent to adjust the parameters of the process window. The typical pre-baking temperature and time are 90-100℃, about 30s. After pre-baking, the silicon wafer will be moved from the hot plate used for baking to a cold plate to return it to room temperature in preparation for the exposure step.

4. Alignment and exposure

The steps after pre-baking are alignment and exposure. In the projection exposure method, the mask is moved to a predefined approximate position on the silicon wafer, or to a proper position relative to the existing pattern on the silicon wafer, and then the lens transfers its pattern to the silicon wafer through photolithography. For proximity or contact exposure, the pattern on the mask will be directly exposed to the silicon wafer by the ultraviolet light source.

For the first layer of patterns, there may be no pattern on the silicon wafer, and the photolithography machine moves the mask relatively to the predefined (chip differentiation method) approximate position on the silicon wafer (depending on the lateral placement accuracy of the silicon wafer on the photolithography machine platform, generally around 10 to 30 μm).

For the second layer and subsequent patterns, the photolithography machine needs to align the alignment mark left by the previous layer exposure to overprint the mask of this layer on the existing pattern of the previous layer. This overlay accuracy is usually 25% to 30% of the minimum pattern size. For example, in 90nm technology, the overlay accuracy is usually 22 to 28nm (3 times the standard deviation). Once the alignment accuracy meets the requirements, exposure begins. The light energy activates the light-sensitive components in the photoresist and starts the photochemical reaction. The main indicators for measuring the quality of photolithography are generally the resolution and uniformity of the critical dimension (CD), overlay accuracy, and the number of particles and defects.

The basic meaning of overlay accuracy refers to the alignment accuracy (3σ) of the graphics between the two photolithography processes. If the alignment deviation is too large, it will directly affect the yield of the product. For high-end photolithography machines, general equipment suppliers will provide two values for overlay accuracy, one is the two-time overlay error of a single machine itself, and the other is the overlay error between two devices (different devices).

5. Post-exposure baking

After the exposure is completed, the photoresist needs to be baked again. Because this baking is after exposure, it is called "post-exposure baking", abbreviated as post-exposure baking (PEB). The purpose of post-baking is to fully complete the photochemical reaction by heating. The photosensitive components generated during the exposure process will diffuse under the action of heating and react chemically with the photoresist, changing the photoresist material that was almost insoluble in the developer liquid into a material that is soluble in the developer liquid, forming patterns that are soluble in the developer liquid and insoluble in the developer liquid in the photoresist film.

Since these patterns are consistent with the patterns on the mask, but are not displayed, they are also called "latent images". For chemically amplified photoresists, excessive baking temperatures or excessive baking times will lead to excessive diffusion of photoacids (catalysts of photochemical reactions), damaging the original image contrast, thereby reducing the uniformity of the process window and line width. A detailed discussion will be carried out in subsequent chapters. To truly display the latent image, development is required.

6. Development

After the post-baking is completed, the silicon wafer will enter the development step. Since the photoresist after the photochemical reaction is acidic, a strong alkaline solution is used as the developer. Generally, a 2.38% tetramethylammonium hydroxide aqueous solution (TMAH) with a molecular formula of (CH₃)₄NOH is used. After the photoresist film has gone through the development process, the exposed areas are washed away by the developer, and the pattern of the mask is displayed on the photoresist film on the silicon wafer in the form of concave and convex shapes with or without photoresist. The development process generally has the following steps:

(1) Pre-spray (pre-wet): spray a little deionized water (DI water) on the surface of the silicon wafer to improve the adhesion of the developer on the surface of the silicon wafer.

(2) Developer dispense (developer dispense): deliver the developer to the surface of the silicon wafer. In order to make all parts of the silicon wafer surface contact with the same amount of developer as much as possible, the developer dispense has developed the following methods. For example, use E2 nozzles, LD nozzles, etc.

(3) Developer surface stay (puddle): After the developer is sprayed, it needs to stay on the surface of the silicon wafer for a period of time, generally from tens of seconds to one or two minutes, in order to allow the developer to fully react with the photoresist.

(4) Removal and rinsing of developer: After the developer has stopped, the developer will be thrown out and deionized water will be sprayed on the surface of the silicon wafer to remove the residual developer and residual photoresist fragments.

(5) Spin dry: The silicon wafer is rotated to a high speed to spin off the deionized water on the surface.

7. Post-development baking, hard film baking

After development, since the silicon wafer is exposed to water, the photoresist will absorb some water, which is not good for subsequent processes such as wet etching. Therefore, hard film baking is required to expel excess water from the photoresist. Since most etching now uses plasma etching, also known as "dry etching", hard film baking has been omitted in many processes.

8. Measurement

After the exposure is completed, the critical dimension (Critical Dimension, CD for short) formed by the lithography and the overlay accuracy need to be measured (metrology). The critical dimension is usually measured using a scanning electron microscope, while the overlay accuracy is measured by an optical microscope and a charge coupled array imaging detector (CCD). The reason for using a scanning electron microscope is that the line width in the semiconductor process is generally smaller than the wavelength of visible light, such as 400 to 700nm, and the electron equivalent wavelength of the electron microscope is determined by the accelerating voltage of the electron. According to the principles of quantum mechanics, the De Broglie wavelength of an electron is

Where h (6.626×10-³⁴Js) is Planck's constant, m (9.1×10-³¹kg) is the mass of the electron in a vacuum, and v is the velocity of the electron. If the acceleration voltage is V, the de Broglie wavelength of the electron can be written as

Where q (1.609×10-19 c) is the charge of the electron. Substituting numerical values, equation (7-7) can be approximately written as

If the acceleration voltage is 300V, the wavelength of the electron is 0.07nm, which is sufficient for measuring the line width. In actual work, the resolution of the electron microscope is determined by the multiple scattering of the electron beam in the material and the aberration of the electron lens. Usually, the resolution of the electron microscope is tens of nanometers, and the error of measuring the line dimension is about 1 to 3nm. Although the overlay accuracy has reached the nanometer level, since the measurement of overlay only requires the ability to determine the central position of the thicker line, an optical microscope can be used to measure the overlay accuracy.

Figure 7.12 (a) is a screenshot of the size measurement taken by a scanning electron microscope. The white double lines and the relative arrows in the figure represent the target size. The image contrast of the scanning electron microscope is formed by the emission and collection of secondary electrons generated by electron bombardment. It can be seen that more secondary electrons can be collected at the edge of the line. In principle, the more electrons collected, the more accurate the measurement. However, since the impact of the electron beam on the photoresist cannot be ignored, the photoresist will shrink after electron beam irradiation, especially the 193nm photoresist. So it becomes very important to establish a balance between measurability and minimal disruption.

Figure 7.12 (b) is a typical schematic diagram of overlay measurement, in which the line thickness is generally 1 to 3 μm, the outer frame side length is generally 20 to 30 μm, and the inner frame side length is generally 10 to 20 μm. In this figure, the different colors or contrasts displayed by the inner and outer frames are due to the differences in the color and contrast of the reflected light caused by the different thicknesses of the different layers of thin films. The measurement of overlay is achieved by determining the spatial difference between the center point of the inner frame and the center point of the outer frame. Practice has proved that as long as sufficient signal intensity is provided, even an optical microscope can achieve a measurement accuracy of about 1 nm.

Lithography process window and pattern integrity evaluation method

Exposure energy margin, normalized image logarithmic slope (NILS)

In Section 2, it was mentioned that the exposure energy margin (EL) refers to the maximum allowable deviation of the exposure energy within the allowable range of line width variation. It is a basic parameter for measuring the lithography process.

Figure 7.13 (a) shows the variation of the lithography pattern with exposure energy and focal length.

Figure 7.13 (b) shows a two-dimensional distribution test pattern with different energies and focal lengths exposed on a silicon wafer. It is like a matrix and is also called the Focus-Exposure Matrix (FEM).

This matrix is used to measure the process window of the photolithography process on one or several patterns, such as energy margin and focus depth. If special test patterns on the mask are added, the Focus-Energy Matrix can also measure other performance parameters related to the process and equipment, such as various aberrations of the lithography machine lens, stray light (flare), mask error factor, photoacid diffusion length of the photoresist, sensitivity of the photoresist, manufacturing accuracy of the mask, etc.

In Figure 7.13 (a), the gray graph represents the cross-sectional morphology of the photoresist (positive photoresist) after exposure and development. As the exposure energy continues to increase, the line width becomes smaller and smaller. As the focal length changes, the vertical morphology of the photoresist also changes. Let's first discuss the change with energy. If the focal length is selected as -0.1μm, that is, the projected focal plane is 0.1μm below the top of the photoresist. If the line width is measured as it changes with energy, a curve as shown in Figure 7.14 can be obtained.

If we select the total CD tolerance of the line width as ±10% of the line width of 90nm, that is, 18nm, and the slope of the line width changing with the exposure energy is 6.5nm/(mJ/cm²), and the optimal exposure energy is 20 (mJ/cm²), then the energy margin EL is 18/6.5/20=13.8%.

Is it enough? This question is related to factors such as the strength of the lithography machine, the ability of process production control, and the requirements of the device for line width. The energy margin is also related to the photoresist's ability to preserve the spatial image. Generally speaking, at the 90nm, 65nm, 45nm and 32nm nodes, the EL requirement for gate layer lithography is 15% to 20%, and the EL requirement for metal wiring layer is about 13% to 15%.

The energy margin is also directly related to the image contrast, but the image here is not the spatial image from the lens, but the "latent image" after the photochemical reaction of the photoresist. The absorption of light by photoresist and the occurrence of photochemical reactions require the diffusion of light-sensitive components in the photoresist film. The diffusion required for this photochemical reaction will reduce the contrast of the image. Contrast is defined as

Among them, U is the equivalent light intensity of the "latent image" (actually the density of the light-sensitive component).

For dense lines, if the spatial period P is less than λ /NA, then its spatial image equivalent light intensity U(x) must be a sine wave, as shown in Figure 7.15, which can be written as

According to the definition of EL, combined with formula (7-10), as shown in Figure 7.16, EL can be written as the following expression, that is,

For equal line and space, CD = P/2. There is a more concise and intuitive expression, namely

That is, if dCD uses the general 10% CD, then the contrast is approximately equal to 3.2 times the EL. The slope in formula (7-11) is

It is also called image log slope (ILS). Due to its direct relationship with image contrast and EL, it is also used as an important parameter to measure the lithography process window. If it is normalized, that is, multiplied by the line width, the normalized image log slope (NILS) can be obtained, as defined in formula (7-15), that is,

Generally, U (x) refers to the spatial image projected by the lens into the photoresist, which here refers to the "latent image" after the photochemical reaction of the photoresist. For dense lines with equal spacing, CD = P/2, and the spatial period P is less than λ/NA, NILS can be written as

For example, for a 90nm memory process, the line width CD is equal to 0.09μm, if the contrast is 50% and the spatial period is 0.18μm, then the NILS is 1.57.

Depth of Focus (Leveling Method)

Depth of Focus (DOF) refers to the maximum range of focal length variation within the allowed range of line width variation. As shown in Figure 7.13, the photoresist will not only change in line width but also in morphology as the focal length changes. Generally speaking, for photoresists with high transparency, such as 193nm photoresists and 248nm photoresists with high resolution, when the focal plane of the photolithography machine is at a negative value, the focal plane is close to the top of the photoresist; when the aspect ratio is greater than 2.5-3, due to the large line width at the bottom of the photoresist, even "undercut" may occur, which may cause mechanical instability and tipping. When the focal plane is at a positive value, due to the large line width at the top of the photoresist groove, the square corners at the top will become rounded (top rounding). This "top rounding" may be transferred to the material morphology after etching, so both "undercut" and "rounding" need to be avoided.

If the line width data in Figure 7.13 is plotted, a curve of line width versus focal length at different exposure energies will be obtained, as shown in Figure 7.17.

The variation of line width with focal length under exposure energy of 16, 18, 20, 22, 24 is also called Poisson plot.

If the allowable variation range of line width is limited to ±9nm, the maximum allowable focal length variation at the optimal exposure energy can be found from Figure 7.17. Not only that, because in actual work, both energy and focal length change at the same time, such as the drift of the lithography machine, it is necessary to obtain the maximum allowable variation range of focal length under the condition of energy drift. As shown in Figure 7.17, a certain allowable variation range of line width EL, such as ±5% as the standard (EL = 10%), can be used to calculate the maximum allowable focal length variation range, which is between 19 and 21 mJ/cm2. The EL data can be plotted against the allowable focal length range, as shown in Figure 7.18. It can be found that in the 90nm process, under the variation range of 10% EL, the maximum focus depth range is about 0.30μm.

Is it enough? Generally speaking, the depth of focus is related to the photolithography machine, such as the focus control accuracy, including the stability of the machine's focal plane, the field curvature of the lens, astigmatism, leveling accuracy, and the flatness of the silicon wafer platform. Of course, it is also related to the flatness of the silicon wafer itself and the degree of flatness reduction caused by the chemical-mechanical flattening process. For different technology nodes, the typical depth of focus requirements are listed in Table 7.1.

Since the depth of focus is so important, leveling, an important part of the lithography machine, is very critical. The most commonly used leveling method in the industry today is to determine the vertical position z of the silicon wafer and the tilt angles Rx and Ry

in the horizontal direction by measuring the position of the light spot reflected by the oblique incident light on the surface of the silicon wafer, as shown in Figure 7.19.

The real system is much more complicated, including how to separate the independent z, Rx, and Ry. Since these three independent parameters need to be measured simultaneously, one beam of light is not enough (there are only two degrees of freedom for lateral displacement), and at least two beams of light are required.

Moreover, if it is necessary to detect z, Rx, and Ry at different points on the exposure area or slit, the number of light spots needs to be increased. Generally, for an exposure area, there can be up to 8 to 10 measurement points. However, this leveling method has its limitations. Because oblique incident light is used, such as a 15° to 20° grazing angle of incidence (or a 70° to 75° incident angle relative to the vertical direction of the silicon wafer surface), for surfaces such as photoresist and silicon dioxide with a white light refractive index of about 1.5, only about 18% to 25% of the light is reflected back, as shown in Figure 7.20, and the other about 75% to 82% of the light entering the detector will penetrate the transparent medium surface. This part of the transmitted light will continue to propagate until it encounters an opaque medium or a reflective medium, such as silicon, polysilicon, metal, or a high refractive index medium, such as silicon nitride, and is then reflected.

Therefore, the "surface" actually detected by the leveling system will be somewhere below the upper surface of the photoresist. Since the back-end-of-the-line (BEOL) mainly has a relatively thick oxide layer, such as various silicon dioxides, there will be a certain focal length deviation between the front-end-of-the-line (FEOL) and the back-end, generally between 0.05 and 0.20 μm, depending on the thickness of the transparent medium and the reflectivity of the opaque medium. Therefore, in the back-end, the design pattern of the chip needs to be as uniform as possible; otherwise, due to the uneven distribution of the pattern density, it will cause leveling errors, which will introduce incorrect tilt compensation and cause defocus.

There are generally two modes for leveling of photolithography machines:

(1) Planar mode: measure the height of several points on the exposure area or the entire silicon wafer, and then find the plane according to the least squares method;

(2) Dynamic mode (exclusive to scanning photolithography machines): dynamically measure the height of several points in the scanned slit area, and then continuously compensate along the scanning direction. Of course, it is important to know that the feedback of leveling is achieved by moving the silicon wafer platform up and down and tilting along the non-scanning direction. Its compensation can only be macroscopic, generally at the millimeter level. Moreover, in the non-scanning direction (X direction), it can only be processed according to the first-order tilt, and any nonlinear curvature (such as lens field curvature and silicon wafer warping) cannot be compensated, as shown in Figure 7.21.

In dynamic mode, some lithography machines can also stop leveling measurement for incomplete exposure areas (shots) or chip areas at the edge of the silicon wafer (an exposure area with a maximum of

can contain many chip areas, called die), and use the exposure or chip area leveling data around it for epitaxy to avoid measurement errors caused by excessive height deviation and incomplete film layer at the edge of the silicon wafer. In ASML lithography machines, this function is called "Circuit Dependent Focus Edge Clearance" (CDFEC).

There are several main factors that affect the depth of focus: numerical aperture of the system, illumination condition, line width of the pattern, density of the pattern, baking temperature of the photoresist, etc. As shown in Figure 7.22, according to wave optics, at the best focal length, all light rays converged to the focus have the same phase;

However, at the defocused position, the light rays passing through the edge of the lens and the light rays passing through the center of the lens travel different optical paths, and their difference is (FF′- OF′). When the numerical aperture increases, the optical path difference also increases, and the actual focal light intensity at the defocus point becomes smaller, or the depth of focus becomes smaller. Under parallel light illumination conditions, the depth of focus (Rayleigh) is generally given by the following formula, that is,

Where θ is the maximum opening angle of the lens, corresponding to the numerical aperture NA. When NA is relatively small, it can be approximately written as

It can be seen that when the NA is larger, the depth of focus is smaller, and the depth of focus is inversely proportional to the square of the numerical aperture.

Not only the numerical aperture affects the depth of focus, but also the lighting conditions. For example, for dense graphics, and the spatial period is less than λ /NA, off-axis illumination will increase the depth of focus. This part will be discussed again in Section 7.1 of Section 7 with off-axis illumination. In addition, the line width of the graphics will also affect the depth of focus. For example, the depth of focus of small graphics is generally smaller than that of coarse graphics. This is because the diffraction wave angle of small graphics is relatively large, and the angle between their convergence in the focal plane is relatively large. As mentioned above, the depth of focus will be smaller. In addition, the baking temperature of the photoresist will also affect the depth of focus to a certain extent. A higher post-exposure bake (PEB) will cause the average of the spatial image contrast in the vertical direction (Z) within the thickness of the photoresist, resulting in an increased depth of focus. However, this is at the expense of reducing the maximum image contrast.

Mask Error Factor

The Mask Error Factor (MEF) or Mask Error Enhancement Factor (MEEF) is defined as the partial derivative of the line width exposed on the silicon wafer with respect to the mask line width. The mask error factor is mainly caused by diffraction of the optical system and will become larger due to the limited fidelity of the photoresist to the spatial image. Factors affecting the mask error factor include lighting conditions, photoresist properties, lithography machine lens aberrations, post-bake (PEB) temperature, etc. In the past decade, there have been many reports on the research of mask error factors in the literature. From these studies, it can be seen that the smaller the spatial period or the smaller the image contrast, the larger the mask error factor. For patterns that are much larger than the exposure wavelength, or in the so-called linear range, the mask error factor is usually very close to 1. For patterns that are close to or smaller than the wavelength, the mask error factor will increase significantly. However, except for the following special cases, the mask error factor is generally not less than 1:

(1) Line lithography using an alternating phase shift mask can produce a mask error factor significantly less than 1. This is because the minimum light intensity in the spatial image field distribution is mainly caused by the 180° phase mutation generated by the adjacent phase zone. Changing the width of the metal line on the mask at the phase mutation has little effect on the line width.

(2) The mask error factor will be significantly less than 1 near the small compensation structure in the optical proximity effect correction. This is because small changes to the main pattern cannot be sensitively identified by the imaging system with limited resolution caused by diffraction.

Usually, for spatially extended patterns such as lines or grooves and contact holes, the mask error factor is equal to or greater than 1. Because the importance of the mask error factor lies in its relationship with the line width and mask cost, it becomes very important to limit it to a small range. For example, for the gate layer with extremely high line width uniformity requirements, the mask error factor is usually required to be controlled below 1.5 (for 90nm and wider processes).

Until recently, obtaining data on mask error factors required numerical simulation or experimental measurement. For numerical simulation, achieving a certain degree of accuracy requires relying on experience in setting simulation parameters. If information on the distribution of mask error factors in the entire lithography parameter space is required, such methods will take a long time to use. In fact, for imaging of dense lines or grooves, the mask error factor has an analytical approximate expression in theory. Under the special conditions that the spatial period p is less than λ /NA and the width of the line is equal to the width of the groove, under annular illumination conditions, the analytical expression can be simplified and written in the following form, that is,

+, - are applicable to grooves and lines, respectively. Among them, σ is the partial coherence parameter (0<σ <1), α is the amplitude transmittance factor in the attenuated phase shifting mask (e.g., for a 6% attenuated mask, α is 0.25), n is the photoresist refractive index (usually between 1.7 and 1.8), and a is the equivalent photoacid diffusion length under the threshold model (depending on the different technology nodes, usually from 5 to 10 nm for 32 to 45 nm nodes to 70 nm for 0.18 to 0.25 μm nodes).

For the alternating phase shifting mask (Alt-PSM), MEF has a simpler expression, namely

Among them, the spatial period p <3λ / (2NA), CD refers to the line width on the silicon wafer, and δ refers to the line width on the mask. If we plot equation (7-21), we can get the result in Figure 7.23. It can be seen that MEF increases rapidly as the spatial period decreases, and increases as the photoacid diffusion length increases.

If all parameters except the photoacid diffusion length in formula (7-21) are known, the diffusion length of the photoacid can be obtained by fitting the experimental data. The results show that after 40 seconds of post-bake, the photoacid diffusion length of a certain type of 193nm photoresist is 27nm; after 60 seconds of post-bake, the diffusion length becomes 33nm. And due to the accuracy of the data, the measurement accuracy of the diffusion length of the photoacid is ±2nm. This is an order of magnitude higher than the accuracy of previous measurement methods, as shown in Figure 7.24. The mask error factor can also be used to calculate the requirements of the mask line width for line width uniformity, as well as the setting of the spacing rules of two-dimensional graphics in the correction of optical proximity effect. For a two-dimensional graphic with shortened line ends, as shown in Figure 7.25, through the calculation of a simple point spread function and a certain degree of approximation of the photoacid diffusion, a nearly analytical formula for the line end optical proximity effect can be obtained, that is,

Where PSF is the point spread function, the subscript "D" represents the diffusion of the photoacid, a represents the photoacid diffusion length, n = 1, 2 corresponds to coherent and incoherent illumination conditions, and

Line width uniformity

Line width uniformity in semiconductor processes is generally divided into: chip area, shot area, wafer area, lot area, and lot-to-lot area. The factors that affect line width uniformity and the general analysis of the impact range are listed in Table 7.2. From Table 7.2, we can find that:

1) Generally, problems caused by lithography machines and process windows have a wide impact.

(2) Problems caused by mask manufacturing errors or optical proximity effects are generally limited to the exposure area.

(3) Problems caused by coating or substrate are generally limited to the silicon wafer.

CMOS devices generally require line width uniformity of about ±10% of the line width. For gates, the general control accuracy is ±7%. This is because in processes below the 0.18μm node, there is generally a line width "trim" etching process after lithography and before etching, which further reduces the lithography line width to the device line width, or close to the device line width, which is generally 70% of the lithography line width. Since the control of the device line width is ±10%, the lithography line width becomes ±7%.

There are many ways to improve the uniformity of lithography line width, such as compensating for the exposure energy distribution in the illumination distribution of the lithography machine based on the exposure uniformity measurement results in the exposure area. This compensation can be achieved at two levels. It can be compensated in the machine constants, which is applicable to all lighting conditions, or it can be compensated in the exposure subroutine (following a certain exposure program). In this way, it can accurately target a certain level with strict uniformity requirements. It can also be improved by analyzing the root cause of the uneven lithography line width. For example, a typical problem is the influence of the height difference caused by the process structure on the silicon wafer substrate on the gate line width uniformity. For example, the local line width uniformity (Local CD Variation, LCDV) of the gate layer discussed in [6] will deteriorate due to the height fluctuation of the substrate. This fluctuation is shown in Figure 7.28.

The line width changes caused by the height difference are shown in Figure 7.29 and Figure 7.30. It can be seen that as the height difference gradually decreases, the line width gradually decreases to a stable value.

1. Improvement of line width uniformity in the chip area or in the graphic area

Since there are many factors affecting this range, only some major methods are discussed.

(1) Improve the process window and optimize the process window.

For dense graphics, off-axis illumination can be used to improve both contrast and depth of focus, and phase-shift masks can be used to improve contrast;

For isolated graphics, sub-diffraction scattering strips (SRAF) can be used to improve the depth of focus of isolated graphics;

For semi-isolated graphics, that is, the spatial period is less than twice the minimum spatial period and slightly larger than the minimum spatial period, the process window here will reach an almost difficult state, also known as "forbidden pitch", as shown in Figure 7.31

As can be seen from Figure 7.31, relative to the minimum spatial period of 310nm, the line width drops from 130nm to about 90nm near the 500nm period. This (not shown here) also involves a significant drop in contrast and depth of focus. The prohibition of spatial period is caused by the need to maintain a fixed minimum line width in the lithography of logic circuits, which results in serious lack of contrast in non-equal spacing imaging in different spatial periods or adjacent patterns. It is mainly caused by Off-axis lighting imposes limitations on semi-dense graphics. Usually, off-axis lighting only has a strong help for the minimum space period, but has a certain negative impact on the so-called "semi-dense" graphics at the minimum space period and 2 times the minimum space period. In order to improve the process window during the so-called forbidden period, the off-axis angle of the off-axis illumination should be appropriately reduced to achieve balanced line width uniformity performance.

(2) Improve the accuracy and reliability of optical proximity effect correction.

The basic process of optical proximity effect correction is: when establishing the model, first design some calibration graphics on the test mask as shown in Figure 7.32. Then, the pattern size of the photoresist on the silicon wafer is obtained by exposing the silicon wafer, and then the model is calibrated (the relevant parameters of the model are determined), and the correction amount is calculated at the same time. Then, based on the similarity between the actual graph and the calibration graph, it is corrected according to the model.

The accuracy of optical proximity effect correction depends on the following factors: silicon wafer linewidth data measurement accuracy, model fitting accuracy, and the rationality and reliability of the model's circuit pattern correction algorithm, such as sampling (fragmentation) method, sampling point density Select, correct step size, etc. For photoresist models, there are generally simple threshold models including Gaussian diffusion (threshold model with gaussian diffusion) and variable threshold resist models. The former assumes that the photoresist is a light switch. When the light intensity reaches a certain threshold, the dissolution rate of the photoresist in the developer changes suddenly. The latter is due to the deviation of the former from experimental data. The latter believes that photoresist is a complex system, and its reaction threshold is related to the maximum light intensity and the gradient of the maximum light intensity (which will cause directional diffusion of the photosensitive agent), and may be a non-linear relationship. And the latter can also describe some etching line width deviations on dense to isolated patterns. Of course, this kind of model cannot physically show the physical image very clearly. Generally speaking, the physical image of the threshold model plus Gaussian diffusion is very clear, and people use it more, especially in process development and process optimization work. In terms of optical proximity effect correction, since it is necessary to build a model accurate to a few nanometers in a very short time, adding some additional parameters whose physical meaning cannot be clearly explained is unavoidable and is also a temporary measure.

Of course, as the photolithography process continues to develop, the photolithography proximity effect correction model will continue to evolve and absorb parameters with physical meanings. In order to increase the accuracy of the model, you can expand the representativeness of the measurement graphics by increasing the number of measurement points (such as 3 to 5 times), that is, improving the calibration (gauge) graphics, as shown in Figure 7.32. The same circuit design graphics are in Correlations and similarities in geometric shapes. During the model fitting process, try to use physical parameters and feed back the fitting errors to the lithography engineer for analysis to eliminate possible errors. Optical proximity effect correction will be discussed in depth in another chapter.

(3) Optimize the thickness of the anti-reflection layer.

Due to the difference in refractive index (n and k values) between the photoresist and the substrate, part of the illumination light will be reflected back from the interface between the photoresist and the substrate, causing interference with the incident imaging light. When this interference is serious, it may even produce a standing wave effect, as shown in Figure 7.33 (c). Figure 7.33 (c) shows the cross-section of the i-line 365nm or 248nm photoresist. Because the distance between the peaks in the standing wave is half a wavelength, and the refractive index n of the photoresist is generally around 1.6 to 1.7, according to the number of peaks (~10), it can be inferred that the thickness of the photoresist is about 0.7 to 1.2μm. The thickness of 193nm photoresist is usually less than 300nm. To eliminate the reflected light at the bottom of the photoresist, a bottom anti-reflection coating (BARC) is generally used, as shown in Figure 7.34 (a). In Figure 7.34 (a), an interface is added after adding the bottom anti-reflection layer. The phase of the reflected light between the anti-reflection layer and the substrate can be adjusted by adjusting the thickness of the anti-reflection layer to offset the reflected light between the photoresist and the anti-reflection layer, thereby eliminating the reflected light at the bottom of the photoresist. For the anti-reflection layer, if strict anti-reflection is to be achieved at a thickness of about 1/4 wavelength, the refractive index n of the anti-reflection layer needs to be precisely adjusted so that it is between nSubstrate and nPhotoresist of the substrate, that is,

(4) Optimize the thickness and swing curve of the photoresist

Even with the bottom anti-reflection layer, there will still be a certain amount of residual light reflected from the bottom of the photoresist. This part of the light will interfere with the reflected light from the top of the photoresist, as shown in Figure 7.35 (a) and Figure 7.35 (b). As the thickness of the photoresist changes, the phase of "reflected light 0" and "reflected light 1" changes periodically, thus causing interference. The redistribution of energy by interference will cause the energy entering the photoresist to change periodically as the thickness of the photoresist changes, so the line width will change periodically as the thickness of the photoresist changes, as shown in Figure 7.35 (b). There are generally several ways to solve the problem of line width fluctuating with photoresist thickness:

Optimize the thickness and refractive index of the anti-reflection layer (select a suitable anti-reflection layer)

Select two anti-reflection layers (generally one of them is an inorganic anti-reflection layer, such as silicon oxynitride SiON)

Add a top anti-reflection coating (Top ARC, TARC) to remove the reflected light on the top of the photoresist

However, adding an anti-reflection layer will make the process more complicated and expensive. When the process window is still acceptable, the thickness with the smallest line width is generally selected. This is because when the thickness of the photoresist shifts, the line width will become larger, not smaller, so that the process window becomes sharply smaller.

2. Other methods to improve line width uniformity

Improve the uniformity of slit illumination, aberration, focal length and leveling control, platform synchronization accuracy and temperature control accuracy of the lithography machine; improve the uniformity of mask line width; improve the substrate and reduce the influence of the substrate on lithography (including increasing the depth of focus and improving the anti-reflection layer). Among them, Section 4.2 mentioned that increasing the uniformity of the design pattern is conducive to improving the accuracy of leveling and actually increasing the depth of focus. The edge roughness of the pattern is generally caused by the following factors:

(1) The inherent roughness of the photoresist: It is related to the molecular weight of the photoresist, the size distribution of the molecular weight and the concentration of the photoacid generator (PAG).

(2) The contrast of the photoresist development dissolution rate with the increase of light intensity: The steeper the change of the dissolution rate with light intensity near the threshold energy, the smaller the roughness caused by partial development.

(3) Photoresist sensitivity: The less the photoresist relies on post-exposure baking (PEB), the greater the roughness of the line width is likely to be. Post-exposure baking can remove some non-uniformity.

(4) Contrast or energy margin of the photolithographic image: The greater the contrast, the narrower the area where the edge of the pattern is developed, and the lower the roughness. It is generally expressed by the relationship between line width roughness and image log slope (ILS).

For chemically amplified photoresists, each photoacid molecule generated by the photochemical reaction will undergo a deprotection catalytic reaction within a range of diffusion length with the generation point as the center of the circle and the radius as the radius. Generally speaking, for 193nm photoresists, the diffusion length is in the range of 5 to 30nm. The longer the diffusion length, the better the pattern roughness when the image contrast remains unchanged. However, near the resolution limit, such as near the 45nm half pitch, an increase in diffusion length will lead to a decrease in spatial image contrast, and a decrease in spatial image contrast will also lead to an increase in pattern roughness.

The dissolution rate of photoresist generally changes from a very low level to a very high level in a step-like manner as the light intensity changes. If this step-like change is steeper, the so-called "partial development" area, that is, the transition area in the middle of the step change, will be reduced, thereby reducing the roughness of the pattern. Of course, too much dissolution contrast will also affect the depth of focus. For some 248nm and 365nm photoresists, a slightly smaller development contrast can extend the depth of focus to a certain extent, as shown in Figure 7.36.

The higher the sensitivity of the photoresist, the shorter the photoacid diffusion length (the higher the fidelity of the aerial image and the higher the resolution), because such photoresists are generally less dependent on post-exposure baking, which may lead to a certain degree of pattern roughness. However, if the concentration of the photoacid generator is increased at the same time, this situation can be improved. Improving the contrast of the photoresist image can reduce the pattern roughness, as shown in Figure 7.37.

The roundness of contact holes and vias is similar to the roughness of the pattern. It is also related to the diffusion of photoacid, the concentration of photoacid, the spatial image contrast, and the contrast of photoresist development. We will not discuss them one by one here.

Photoresist morphology

Abnormalities in photoresist morphology include sidewall tilt angle, standing wave, thickness loss, bottom footing, bottom incision, T-top, top rounding, line width roughness, aspect ratio/pattern dumping, bottom residue, etc. We will discuss them one by one, as shown in Figure 7.38.

Sidewall angle: This is generally because the light entering the bottom of the photoresist is weaker than the light at the top (due to the absorption of light by the photoresist). The solution is generally to reduce the absorption of light by the photoresist while increasing the sensitivity of the photoresist to light. This can be achieved by increasing the addition of photosensitive components and increasing the catalytic effect of photoacids in the deprotection reaction (diffusion-catalysis reaction). The sidewall angle will have a certain impact on etching, and in severe cases, the sidewall angle will be transferred to the etched substrate material.

Standing wave: The standing wave effect can be effectively solved by adding an anti-reflection layer and appropriately increasing the diffusion of the photosensitizer (such as by increasing the temperature or time of post-baking to increase the diffusion of photoacids).

Thickness loss: Since the top of the photoresist receives the strongest light and the top is exposed to the most developer, the thickness of the photoresist will be lost to a certain extent after the development is completed.

Footing: The bottom footing is generally caused by the acid-base imbalance between the photoresist and the substrate (such as the bottom anti-reflection layer). If the substrate is relatively alkaline or hydrophilic, the photoacid will be neutralized or absorbed into the substrate, causing the deprotection reaction at the bottom of the photoresist to be compromised. The solution to this problem is generally to increase the acidity of the substrate, increase the pre-exposure baking temperature of the photoresist and the anti-reflective layer, so as to limit the diffusion of the photoacid in the photoresist and into the substrate. However, limiting the diffusion will also affect other properties, such as the roughness of the pattern, the depth of focus, etc.

Undercut: Contrary to the bottom footing, undercutting is due to the higher acidity at the bottom of the photoresist, and the deprotection reaction at the bottom is higher than that in other places. The solution is exactly the opposite of the above.

T-topping: T-topping is caused by the alkaline (base) components in the air in the factory, such as ammonia, ammonia (ammonia), and amine organic compounds (amine), which penetrate into the top of the photoresist and neutralize part of the photoacid, resulting in a larger local line width at the top, and in severe cases, it will cause line adhesion. The solution is to strictly control the alkali content of the air in the photolithography area, usually less than 20 ppb (parts per billion), and try to shorten the time from exposure to post-exposure delay.

Top rounding: Generally, the light intensity irradiated on the top of the photoresist is relatively large. When the development contrast of the photoresist is not very high, this part of the increased light will lead to an increased dissolution rate, thus causing the top to round.

Linewidth roughness: Linewidth roughness has been discussed before.

Aspect ratio/pattern collapse: The aspect ratio is discussed because during the development process, the developer, deionized water, etc. will generate lateral tension formed by surface tension in the photoresist pattern after development, as shown in Figure 7.39. For dense patterns, since the tension on both sides is roughly the same, the problem is not too big. However, for the pattern at the edge of the dense pattern, if the aspect ratio is large, it will be subject to unilateral tension. Coupled with the disturbance of high-speed rotation during the development process, the pattern may collapse. Experiments show that a height-to-width ratio above 3:1 is generally more dangerous.

Scumming: The reason for scumming is generally that the bottom photoresist does not absorb enough light, resulting in partial development. In order to improve the resolution of the photoresist, the diffusion length of the photoacid needs to be minimized, and the spatial development uniformity caused by the diffusion of the photoacid is reduced. In this way, the roughness of the space increases. The bottom scumming can generally be reduced by optimizing the lighting conditions, mask line width bias, and baking temperature and time to improve the spatial image contrast and increase the exposure per unit area.

Alignment and overlay accuracy

Alignment refers to the registration between layers. Generally speaking, the overlay accuracy between layers needs to be around 25%~30% of the critical size (minimum size) of the silicon wafer. Here we will discuss the following aspects: overlay process, overlay parameters and equations, overlay marks, equipment and technical issues related to overlay, and processes that affect overlay accuracy.